SYDNEY: As China increases lending to other developing countries, ‘debt trap’ charges are growing quickly. As it greatly augments financing for development while other sources continue to decline, condemnation of China’s loans is being weaponized in the new Cold War.

Debt-trap diplomacy?

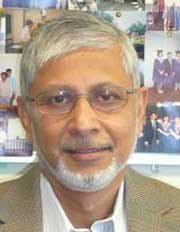

The catchy term ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ was coined by Indian geo-strategist Brahma Chellaney in 2017. According to him, China lends to extract economic or political concessions when a debtor country is unable to meet payment obligations. Thus, it overwhelms poor countries with loans, to eventually make them subservient.

Unsurprisingly, his catchphrase has been popularized to demonize China. Harvard’s Belfer Center has obligingly elaborated on the rising Asian power’s nefarious geostrategic interests. Meanwhile, as with so much else, the Biden administration continues related Trump policies.

But even Western researchers generally wary of China dispute the new narrative. A London Chatham House study concluded it is simply wrong – flawed, with scant supporting evidence.

Studying China’s loan arrangements for 13,427 projects in 165 countries over 18 years, AidData – at the US-based Global Research Institute – could not find a single instance of China seizing a foreign asset following loan default.

China has been the ‘new kid on the block’ of development financing for more than a decade. Its growing loans have helped fill the yawning gap left by the decline and increasing private business orientation of financing by the global North.

Instead of tied aid pushing exports, as before, it now shamelessly promotes foreign direct investment from donor nations. Unless disbursed via multilateral institutions, China’s increased lending to support businesses abroad has not really helped developing countries cope with renewed ‘tied’ concessional aid.

Grand ‘debt trap diplomacy’ narratives make for great propaganda, but obscure debt flows’ actual impacts. Most Chinese lending is for infrastructure and productive investment projects, not donor-determined ‘policy loans’. Some countries ‘over-borrow’, but most do not. Deals can turn sour, but most apparently don’t.

While leaving less room for discretionary abuse in implementation, project lending typically puts borrowers at a disadvantage. This is largely due to the terms of sought-after foreign investment and financing, regardless of source. Hence, the outcomes of most such borrowing – not just from China – vary.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port is the most frequently mentioned China debt trap case. The typical media account presumes it lent money to build the port expecting Sri Lanka to get into debt distress. China then supposedly seized it – in exchange for providing debt relief – enabling use by its navy.

But independent studies have debunked this version. Last year, The Atlantic insisted, ‘The Chinese “Debt Trap” Is a Myth’. The subtitle elaborated, “The narrative wrongfully portrays both Beijing and the developing countries it deals with”.

It elaborated: “Our research shows that Chinese banks are willing to restructure the terms of existing loans and have never actually seized an asset from any country, much less the port of Hambantota”.

The project was initiated by then President Mahindra Rajapaksa – not China or its bankers. Feasibility studies by the Canadian International Development Agency and the Danish engineering firm Rambol found it viable. The Chinese Harbour Group construction firm only got involved after the US and India both refused Sri Lankan loan requests.

Sri Lanka’s later debt crisis has been due to its structural economic weaknesses and foreign debt composition. The Chatham House report blamed it on excessive borrowing from Western-dominated capital markets – not Chinese banks.

Even the influential US Foreign Policy journal does not blame Sri Lanka’s undoubted economic difficulties on Chinese debt traps. Instead, “Sri Lanka has not successfully or responsibly updated its debt management strategies to reflect the loss of development aid that it had become accustomed to for decades”.

As the US Fed tapered ‘quantitative easing’, borrowing costs – due to Sri Lanka’s persistent balance of payment problems – rose, forcing it to seek International Monetary Fund help. Some argue borrowing even more from China is the best option available to the island republic.

To set the record straight, there was no debt-for-asset swap after Sri Lanka could no longer service its foreign debt. Instead, a Chinese state-owned enterprise leased the port for US$1.1 billion. Sri Lanka has thus boosted its foreign reserves and paid down its debt to other – mainly Western – creditors.

Also, Chinese navy vessels cannot use the port – home to Sri Lanka’s own southern naval command. “In short, the Hambantota Port case shows little evidence of Chinese strategy, but lots of evidence for poor governance on the recipient side”.

Malaysia

China has also been accused by the media of seeking influence over the Straits of Malacca, through which some 80% of its oil imports pass. Debt-trap proponents claim Beijing therefore inflated lending for Malaysia’s controversial East Coast Rail Link (ECRL).

The Chatham House report notes, “The real issue here is not one of geopolitics, but rather – as in Sri Lanka – the recipient government’s efforts to harness Chinese investment and development financing to advance domestic political agendas, reflecting both need and greed”.

ECRL was initiated by convicted former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak. Ostensibly to develop the less developed East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, it rejected other less costly, but much needed options.

Borrowings are far more than needed – probably for nefarious purposes. Loan terms were structured to delay repayment – to Najib’s political advantage by ‘passing the buck’ to later generations. But such abuse is by the borrower – not the lender – unless Chinese official connivance is involved.

Non-alignment for our times

There is undoubtedly much room for improving development finance, especially to achieve more sustainable development. Instead of mainly lending to the US, as before, China’s growing role can still be improved. To begin, all involved should respect the United Nations’ principles on responsible sovereign lending and borrowing.

After more than half a century of Western donors’ largely betrayed promises, China’s development finance has significantly improved ‘South-South cooperation’. Meanwhile, sustainable development finance needs – compounded by global warming, the pandemic and Ukraine war – have increased.

After decades of the West denying China commensurate voice in decision making, even under rules it made, its role on the world stage has grown. But instead of working together for the benefit of all, rich countries seem intent on demonizing it. Unsurprisingly, most developing country governments seem undeterred.

As the new Cold War and the scope of economic sanctions spread, collateral damage is undermining development finance and developing countries. To cope with the new situation, developing countries need to consider building a new non-aligned movement for our dark times.